In late June, Chicago artist Amie Sell’s installation, Home Sweet Home, was unilaterally censored and removed from the Milwaukee Avenue Arts Festival by landlord and businessman Mark Fishman due to its criticism of M. Fishman and Co.’s role in the gentrification of the Logan Square neighborhood. The incident was covered in the Chicago Reader.

* * *

Adam Turl: Before talking about the incident at the Milwaukee Avenue Arts Festival (MAAF), I wanted to ask you to discuss your work more generally; this would include the relationship of your artwork to your community activism in Logan Square. According to the Chicago Reader you have lived in the neighborhood for more than nine years and you helped organize Somos Logan Square (We are Logan Square).

Amie Sell: Around 2010, I started a long-term art project that examines House/Home: A house being a container, structure and financial tool. A home being a collection of the intangibles: feelings of safety and security, relationships, emotions and memories. This examination began out of personal introspection and the realization that I have lived in 25 different structures and moved 27 times in my short life. In comparison with many people, this is unusual, but has just been how my life has unrolled; Growing up in rental situations, being part of a military family, independently working my way through college and for the last 9 years living in the 60647 zip code.

Logan Square has become my community home. I’ve grown here professionally and artistically. It has given me a place to thrive and carve out a stable sense of being while being a renter. I would love to own a house here, but the uncertainty of life and financial means have escaped me. Renters are often viewed as transient and Chicago in generally does have a very transient population of which one of the demographics that belong to: white, college educated, an artist, from a small Midwestern town. Chicago is a brain drain of young professionals looking for work, culture and experience – the typical gentrifiying population. Many leave when they decide to grow their own family, finding the state of the public education deplorable, housing prices and taxes to be too high and endemic violence and poverty too much raise their children around. They come for the fun and leave when it gets real.

My installation Home Sweet Home that was to be shown at MAAF was the first time that I intentionally mixed my activism and art. There are threads in my art practice that honor moments of violation and thresholds of change, but my work is typically more benign and experimental as I figure out what it is that I am trying to create as a sculptor. Creation is a fluid process for me, typically involving the act of research, deep thought, gathering of materials and defining parameters and process.

In January 2014, I heard about mass evictions happening in my neighborhood. Tenants in a number of buildings were being handed 30-day notices to pay more rent ($250+/mo.) or to move out – in the cold polar vortex winter. My gut reaction was that it was straight up inhumane. People were being evicted from buildings with large numbers of units with reasonable rents that households could afford without becoming housing burdened. These households were a mix of long-term renting families, single mothers, individuals on fixed incomes and working-class wage earners. Tenants from these buildings were organizing and making their voices heard, so I volunteered to do some flyering and showed up in solidarity at their protest. As a life-long renter, as an empathetic human who understands the fear of having your home disrupted, as a neighbor who has observed the neighborhood changing slowly to serve a higher class of people, I was inspired to join in their cause. Moving and having your life disrupted is a stressful situation. Standing up in the face of fear inducing land lords takes courage and bravery. Pricing out renters with threats of eviction is just one of many tactics that egregious land lords use in hopes to make the poor masses scatter. It might be legal by Illinois State law, but it does not make it right or just.

This action inspired me to listen more closely, participate in meetings, build relationships and research this topic as both an activist and as an extension of my long-term my House/Home artistic project. Eight months later, we have formed the grassroots organization We Are/Somos Logan Square – the chant used when the evictees stood up against their evictor, Mark Fishman. We organize tenants in other buildings, conduct outreach, share information, take actions and connect with other organizations and individuals to reach our goals. Those goals set by the group are to 1) save affordable rental units and create co-op housing 2) keep the neighborhood diverse; both culturally and socio-economically 3) to support community driven, balanced changes to the neighborhood.

House/Home

AT: Mark Fishman — who owns multiple buildings in Logan Square — is a board member, treasurer and financier of the Independent Artists and Merchants of Logan Square (I AM Logan Square) which runs the MAAF. Fishman also owns the Logan Theater (and received one million dollars in TIF funds to renovate it). And Fishman “donated” several spaces to the MAAF. He is also involved in the effort to displace Logan Square’s residents and bring in a larger number of young, upscale residents. In June you were accepted into the fair—and some of your work was evidently featured in MAAF promotions. Can you discuss how you conceived of Home Sweet Home in relationship to the space you were awarded (belonging to M. Fishman and Co.) and the ongoing struggles in the neighborhood (including Fishman’s role in those struggles)?

AS: The idea to enter MAAF was given to me at a picnic that I hosted when we were first establishing We Are/Somos Logan Square. The idea of hosting picnics came out of organizing meetings. My logic was that picnics are an inclusive way to create regular gatherings where people can connect in person and become aware of the implications of gentrification and become informed about local housing issues, all in hopes to inspire action. The action inspired to me from the first picnic was to enter MAAF, the community art festival, and make a site-specific installation to extend my previous work house/home work into the realm of community.

MAAF awarded me a storefront space at 2779 N. Milwaukee Ave., ten days before the festival opened. The uncertainty of which space I would get left me to keep my ideas loose: I contacted other artists to see anyone wanted to collaborate, mulled over how subtle I wanted to be, yet present an impactful piece at a three-day festival in a dilapidated space slated for remodeling.

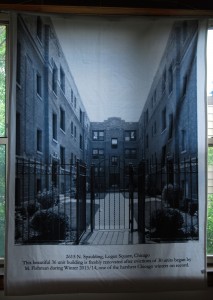

My creative process had begun earlier by taking pictures of the architecturally beautiful buildings where the winter evictions had taken place and where new evictions were looming by the same developer. When they handed me the keys to the space it fully dawned on me that it was the same building as 3335 W. Diversey – a former SRO where some evictions where in process – that I had already photographed. It is confusing because it is one of those iconic flat iron buildings at the six corner crossings along Milwaukee Ave.’s diagonal cut through the Northside. The storefronts have Milwaukee Ave addresses. The apartments above have Diversey Ave addresses. Knowing that I was going to create an installation in the same exact building that people are being evicted from sent a surge through me. It doesn’t get any more site-specific than that and anyone who creates or appreciates installation artwork understands that serendipity of the connection. It still makes me a little dizzy and nauseated when I think about that conceptual layer that fell into my lap.

The time crunch and no budget to prepare and install led me to make a big, blatant statement. The creation of a memorial honoring the violation of the evictions seemed the most viable. I had four large fleece blankets (symbols of security) printed with the photos capturing the beauty of the architecture as capsules of history and juxtaposing them with short factual statements of the evictions. Also, I created a large collage and repurposed a chair by adding stitch work words ‘home sweet home’ in five languages of different immigrant groups that have landed in the area, as nods to remembering the often forgotten, unrecorded lives that passed through the walls of rental buildings. It was my way of paying homage to the current and past history of these homes before all is swept up with the dust and paint chips and lost forever.

Mark Fishman is a suburban-living developer and businessman who mainly works in Logan Square. In Logan Square, he owns around 52 properties that includes around 1,100 rental units, the recently renovated with tax-payer TIF funds Logan Theatre, trendy Parson’s Chicken and is the board Treasurer of the arts-based non-profit I AM Logan Square. At face value, it seems like he is just trying to make the neighborhood better. If you scratch below the thin surface, do your research and talk to people in the neighborhood, everyone has a story to tell you about how he has impacted their life, most in a negative way. Please check out his Yelp reviews. My work was not intended to demonize him, it was to take a stand by allowing the audience to look at those cold harsh facts and make their decision. He evicted people to benefit his property business, M. Fishman Co. He evicted my work from the local art festival. Making unilateral moves to change the fabric of our neighborhood for his capital gain is his mode of operation. He uses his image as an art patron and as a tool for gentrification. It is our duty as citizens to check his power.

AT: In both a specific and general sense how do you characterize the relationship between art, the “art world” and gentrification? Ryan Harte recently argued on the infinite mile website in an article Red Wedge reposted, that gentrification is both an economic and aesthetic process by which the value that artists bring to an urban space is mostly separated from both artists and community members (and of course these categories overlap). That value is given to the space itself and this largely benefits real estate developers, landlords and the influx of wealthier residents. What does this mean for artists, such as yourself, who criticize the process of gentrification directly in your work — and artists in general?

AS: The relationship of the art world and gentrification is often viewed simply as a chicken and egg scenario. Ryan Harte’s article is great and helps the dialogue around gentrification get a little closer to clarity on this seemingly elusive situation. Thank you for sharing it with me.

Art is often boiled down to aesthetic appeal to be a consumed, a commodity of sorts. Artists find beauty in decay, chaos, blight and create value out of the mundane, the neglected. Chicago neighborhoods have plenty of neglect and inspiring remnants for artists to create nests and charge themselves with creative potential.

For me, art isn’t so much about creating something out of nothing or seeking original thought, it’s a way of experiencing and sharing the world, finding potential and purpose. Upcycling, reuse, repurposing, DIY have all become pop culture words that come out of the human creative desire to make the physical world better with our own intuition, skill and hand. Making something is a powerful force. It empowers our spirit, builds confidence and gives way to feeling useful. This is true value.

Our economy attaches monetary value to these creations. Typically, the easier to consume, the more aesthetic and coveted, the higher the market value an art object can obtain. Using only this metric to define the value of art has an inherit corruption about it. Art created for purely aesthetic reason and easy consumption is valid, but art with purpose and thought that evokes feelings has true power, something that a price tag cannot be put on. Once art it is capitalized upon by ancillary parties and separated from the artists intentions, that inherit spirit value is often lost. If art history teaches us anything, it is that people will capitalize on artists, dead or alive.

Artists live everywhere. A supportive neighborhood full of artists creates a certain inherent value. Developers, marketing teams and business people in conjunction with the media feed people dreams and illusions of grand coolness by proximity. That mystic bohemian atmosphere is an easy marketing tool to lure the young professional crowd. This is where the displacement begins. In many ways, I am culpable in this situation by choosing my lifestyle to experience the world, but it is my duty as an artist and activist to help create new metrics and fight for regulations that stop displacement. We need to create new ways of calculating net worth and value capture methods to sustain ourselves, our neighbors and our communities. This is the only way to change the destructive forces often associated with gentrification.

Milshire SRO blanket

AT: Formally, the festival refused to censor you and Geary Yonker supported your free speech rights. It was an employee of M. Fishman and Co. that took down your work — without your permission or the permission of MAAF. What do you think this says about the relationship of art to social class and economic power in the U.S. (which spends far less in public resources on the arts than virtually every other wealthy industrialized nation)? And what does this mean for free speech in art?

AS: Geary Younker and IALS were complicit in the removal of my work in an attempt to hide the truth of their benefactor, donor, Board Treasurer and landlord. In conversation and statements to media, Mr. Younker has defended my right to free speech with words. But with his actions as the President of an arts organization, he has failed me by not securing different location for my work, instead letting it be removed and not seen by the community. He has also failed me by not honoring my repeated requests to meet with the entire organizational board to discuss the matter. Apparently, they do not meet regularly and my artworks removal is not a big enough topic to warrant a meeting. In fact, a friend dug up a 2012 990 tax form to help me find out who is actually on their board. It is not posted on their website, like most 5013.c grant accepting organizations. After discovering this form, I asked Mr. Younker to confirm and give me the contact info for the individuals so I could create an official appeal to be heard. He returned with one member’s contact information, Peter Creig Toalson, who was kind enough to meet with me and apologize, despite being a business partner of Mark Fishman.

Before the festival, I was aware that Fishman was the landlord of the space I was installing in and that he was affiliated with IALS. But it wasn’t until after the removal that I started to piece together his deep involvement in the organization of which many details are still murky. People have accused me of “biting the hand that fed me.” Sure, I clearly insulted the landlord of the space with the reality that he evicts people. His reaction was to evict me. This clearly shows me that he feels he can do whatever he wants in the community without our input. But luckily, the community is much more than just its buildings, it is the people, lives and energy in the spaces between the walls. Countless people have reached out to me to show support and to collaborate in an overwhelmingly beautiful way. By ‘biting the hand’, I learned that many others were there to feed me.

For me, this incident is one of many that are continually redefining art’s place in the world. Slowly artists are renegotiating the old system of control out of the charitable, benevolent philanthropist model and the economic power structures that frame it. These powers might lash out, but reactionary moves always backfire.

Being an artist in the United States is not a living wage profession and is not readily accepted as part of the normal business driven work world. It is an ‘other’, secondary to a day job or something allowed only after your basic needs are met with another source of income. I often tell people that I work a day job to support my art habit. But, I suppose this is where I find my freedom to create as I wish. It took me a long time to reconcile this and my art does not have to be a commodity, as it is not beholden to anyone.

AT: How can artists, who often face their own economic precariousness, connect and solidarize with the economic and social problems facing the working-class, the poor and people of color in Chicago and elsewhere?

AS: The artist Joseph Bueys has always been an inspiration for me: “Only on condition of a radical widening of definition will it be possible for art and activities related to art to provide evidence that art is now the only evolutionary-revolutionary power. Only art is capable of dismantling the repressive effects of a senile social system to build a SOCIAL ORGANISM AS A WORK OF ART.” *

Use your art to connect. Widen its definition. Quit supporting the powers that seek to disconnect. Be smart about what organizations truly support your endeavors and what you give them. Get involved, listen and act. You do not exist in a vacuum, nor does your art, even though it might feel like it sometimes. That ‘character’ that people find cool about your neighborhood or the ‘beauty’ of the painting bought to match a couch are micro symptoms of unbalanced, unchecked power structures and materialism. It is our duty as artists, as humans, as neighbors, as people who believe in equality and balance to stand up. As artists we are always evolving, honing our skills, rehearsing as individuals to create a world better. If we do not harness our creative abilities to be positive forces of change, who will?

AT: You mentioned the social sculpture of Joseph Beuys. In my opinion Beuys is one of the most important artists of the post-World War II period, and one of the most underrated in North America, both due to a certain amount of American art-world chauvinism (at that time) and later “left-wing” critiques of his work. Most importantly this includes Benjamin Buchloh’s essay in October, “Beuys: The Twilight of the Idol” in which he argued that Beuys was a crypto-fascist, anti-scientific and reactionary. In my opinion Beuys deals with something else: the relationship of human subjectivity to both the social and spiritual processes of art, on both a mythological and a political level. For Beuys the “readymades” of Marcel Duchamp do not become (as immediately) commodity fetishes but a different kind of fetish–a kind of record, a “magical” record of their interactions with people. I am curious if you have any thoughts on Buchloh’s critique of Beuys. And if you are so inclined, to elaborate on the way in which Beuys’s method influences your method. Feel free to totally disagree with me of course.

AS: I connected to Joseph Buey’s art by living amongst his piece 7000 Oaks during my 2002 summer internship on scholarship at Documenta 11 in Kassel, Germany. Every morning I caught the bus by an oak tree paired with a basalt stone. The entire installation dots the city and every time I encountered one of these spots, it remind me of the connection between the natural and built world and how together we can begin to heal wounds of the past and grow in mature ways. I have never read any criticism of this particular installation because I’ve never wanted to taint my visceral experience with it. In fact, I rarely read any art criticism, instead preferring to experience art in person or in pictures and feel it visually. Reading Clement Greenberg in college gave me a lingering disdain for the way critics, especially of that era, have the ability to reinforce the sterile. old-boys club notions and sophistications of the fine art world.

As far as Buchloh’s criticism, I tried to put myself in his shoes and understand why he extrapolated that “Beuys was a crypto-fascist, anti-scientific and reactionary,” but failed.

1) Crypto-facist: I disagree almost completely with this notion, except for the caveat of the thoughts that Slavoj Zizek has imprinted in my brain (paraphrasing) that we are all secretly fascist, wanting the world fit our own vision. 2) Anti-scientific: Bueys’ work has mythic and metaphysical properties to it, of which inherently I feel connected to. His background story might be fictional, but so are many works that uphold human narratives that give people purpose and feeling of security. The fields of Art and Science overlap in many ways: searching for truth, collection, setting parameters, measurement, fostering of curiosity, etc. The means that they use to achieve those goals are different. Bueys’ work uses physical objects to conjure space and places that we cannot see with our eyes. In my opinion, that is not so different than the work of say particle physicists, just different modes. 3) Reactionary – sure, what art is devoid of reaction? The degrees of reaction, the directness and context will always vary. Something always compels creation; whether it is something as dramatic your life being saved by being wrapped in fat and felt after your plane was shot down in Russia or something as mundane as a seed sprouting into a plant. Artists and humans are always reacting.

AT: I understand you are recreating your installation Home Sweet Home in Logan Square. Can you tell me about that process, and let folks know where and how they can see the work?

AS: After my work was removed from MAAF, artists, curators and the community members of Logan Square surprised me with many offers and have been extremely supportive. Kitchen Space Gallery, an artist-run space in a kitchen contacted me in a sincere way and has been showing a couple of the pieces for most of August. A community member, Monique Gilbert, is opening her home to me for a couple weeks in September to show the installation in its entirety. At the end of September during, A Day in Avondale festival, the pieces will be part of a collaborative curating effort with a group of artists that reached out to me the aftermath of the debacle. A panel discussion presented by A Voice in the City will also accompany that show. It will be bringing together local leaders with various knowledge bases to begin to discern between notions of house and home to seek community solutions. It is still being planned and should be a new twist on the sometimes exhausted and circular conversation about affordable housing.

2615 N. Spaulding Blanket

AT: Can you tell us what you are working on next — both in terms of your artwork and community activism in Logan Square?

AS: In terms of my artwork, I have been offered a three-month artist residency at Grace Church in the neighborhood. There I will be connecting with their young, small and humble community of members who most have been disenfranchised by their previous churches and faith experiences. As a person often turned off by organized religion, I’ve surprised myself by accepting their invitation. My work around affordable housing has opened me up to the greater community in ways that the younger riot girrrl inside me would have out-right rejected. I had a pivotal late-night conversation with a Lutheran Pastor in an alley of the Public House Co-op Bar in Riverwest, Milwaukee earlier this summer that set me straight about working with churches on issues, despite lacking the faith bone and dropping preconceived notions. Grace Church invited me in and we had an open and honest discussion about our intentions and possibilities, which was refreshing and enlightening. Who knows, maybe they are looking to be radicalized? Maybe they will radicalize me more?

This residency will give me some space, mentally and physically to continue working on my incomplete House/Home project. I have many drawings and models to complete. It will also give me the opportunity to further figure out how these notions can translate in to community settings, breaking from their deeply personal roots.

As far as activism, We Are/Somos Logan Square is creating every opportunity we can to further the dialogue and facilitate actions to slow gentrification’s negative effects in our part of the world. We are slowly but steadily making a presence and aligning with other community groups and members that are looking for a little more of a grass root and radical experience to facilitate change. It seems now that my artwork and activism have connected and will be growing simultaneously in ways that I can only imagine.

* source of his art statement on his concept of Social Sculpture and Social Architecture: ‘I am searching for field character’, 1973; in “Energy Plan for the Western man – Joseph Beuys in America –”, compiled by Carin Kuoni, Four Walls Eight Windows, New York, 1993, p. 22