[1]

For business I turn to the Wall Street Journal. Their lead editorial declares that governance by the people is insufficient and unfair to the captains of industry. The Devine Right of Kings should be extended to CEOs, and employees notified of their new serfdom. Microsoft’s nuclear arsenal has grown tenfold over the last decade, but Apple’s portable nuclear devices are more user-friendly; come in hip colors, and are being installed in the nation’s schools to improve pedagogy and weaken the teachers’ union. - Mark Miller, The Librarian at the End of the World [2]

“Oh, my God, Eema!” Gib shouted between the cop’s useless, weakening protests. “Cops taste like betrayal! No guilt at all!” She bent forward and kept eating. - Tish Markley, “Space Goths” [3]

***

The default cultural logic of neoliberalism and the political center is capitalist realism. In response the cultural logic of working-class emancipation (socialism) is critical irrealism.[1] The ir – or no – of critical irealism is opposed to a particular kind of realism. Therefore, we should examine it more closely.

from Locust Review #1

Cover of Locust #1

Anupam Roy, Brahmin Colonizer’s Apparatus, from Locust Review #1

It can be argued, of course, that all realism is, in its basic form, undialectical and therefore not socialist, trapped in empirical moments, drawing limited conclusions from the most partial of information. The realist lens sees the man “camping” under a viaduct a few blocks from the Las Vegas Strip. It does not see his biography. It does not see his dreams. It does not see his victories, his defeats, his lost loves, his former or present employment. The realist lens does not see the drawings he made when he was eight years old. It does not see him standing up for a fellow Marine targeted for being gay. It does not seem him protest the war. It does not see him at his worst; because his worst is not his mere material poverty. It is something else; something so secret he doesn’t share it with anyone. Nor does the lens see him at his best. That too is secret.

The realist lens, in this sense, sees almost nothing.

Or, in an example we have noted before: Videos of police brutality, racism, and violence, on the one hand “prove” the decades-long narratives of Black people, people of color, and the poor. The constantly mounting evidence has had little impact on the capitalist state. But there is a secondary problem. Videos of police terror, because they are plucked from the larger metanarrative of a racist capitalism, conceal something. They conceal the objective weakness of the police. They conceal that, under conditions of solidarity and class consciousness, the police are vastly outnumbered by the class and by the specific groups they oppress. In this way, these videos act as disciplinary images. They give us, in part, an illusion of our weakness, an exaggeration of police power, while often retraumatizing the victims of the police. This is not to say we shouldn’t record and document police racism and violence. We should. If only to try to protect the specific human beings they are attacking. Nevertheless, the way these images work in communicative capitalism is highly contradictory.

Partial installation view of the Locust Review affiliated Born Again Labor Museum organized by Tish Markley and Adam Turl (2019)

Still from the Born Again Labor Museum video Galapagos, Illinois

Installation and collaborative discussion organized by Anupam Roy.

Capitalist realism in particular posits an even more limited framework than realism more generally. Nothing imaginary is possible unless it fits, somehow, within the logic of capital accumulation and economic growth. This particular strand of realism has, over the course of forty years, infected every aspect of social being. No cultural enterprise, no political policy, no personal aspiration, no work or leisure time, no child rearing, no elder-care, no protest, escapes its ruthless “logic.”

Moreover, this logic infects our arts and literature. The stories we tell in much mainstream culture are increasingly inflected with a universal cynicism that alternates between saccharine falseness (often in stories about the private realm; often the realm of the reproduction of labor) and gritty tales (of the public realm) that serve as moral retellings of capitalism’s origin story (from the capitalist point of view). Think here of Hallmark movies on the one hand, and much prestige television on the other.

In the “art world” it has produced a particular sort of realistic blandness.

"When hippies rose from their supine hedono-haze to assume power (a very short step),” Mark Fisher writes, “they brought their contempt for sensuality with them.”

Brute functional utilitarianism plus aesthetic sloppiness and an imperturbable sense of their own rights are the hallmarks of bourgeois sensibility... What we find in Emin, Hirst, Whiteread, and whoever the idiot was who rebuilt his dad's house in the Tate is a disdain for the artificial, for art as such, in a desperately naif bid to (re)represent that pre-Warholian, pre-Duchampian, pre-Kantian unadorned Real. Like our whole won't-get-fooled-again PoRoMo culture, what they fear above all is being glamoured. [4]

Anupam Roy’s Stateless Militia series (which will appear in Locust #2)

Whether Fisher’s antipathy for hippies is entirely fair, he is correct that the bourgeoisie has learned to fear the sensual and seductive aspects of art itself; that which exists beyond their banal Real. This preference for the Real – and suspicion of seduction – is not new for the bourgeois. As John Berger notes in Ways of Seeing, in his response to a mainstream critic’s mystification of the 17th century Dutch painter Frans Hals:

He speaks of seduction despairingly. Yet what is this seduction? It is nothing less than the painting working on us... It’s as though he doesn’t want us to make sense of it on our terms. [5]

In what seems like a paradox, it is capitalist “realism” that is an illusion. As Mark Fisher writes, “capitalist realism can be understood as a kind of dreamwork.”[6] Or, for the working-class, often a nightmare-work. Citing Leon Festinger’s ideas about cognitive dissonance -- in particular the idea that those with false ideas often double-down on them when confronted with conclusive counter-evidence -- Fisher notes the historic role of neoliberalism and capitalist realism in attacking (and exploiting the contradictions of) the democratic and libertarian socialist rebellions of the 1960s and 1970s.[7] In this way, capitalist realism is a curse cast upon the rebellious working-classes of the 1970s; a curse passed down from our parents to their children.

This curse must be dispelled.

A WARNING AGAINST INDIVIDUAL SOLUTIONS. Left: BALM’s Born Again Labor Tract as it appears in Locust #1. Above: The glitched IRL “Born Again Labor Tract” as it appears in BALM’s secret Nevada storage facility.

“You, *Doctor Hiroguchi,” she went on, “think that everybody but yourself is just taking up space on this planet, and we make too much noise and waste valuable natural resources and have too many children and leave garbage around. So it would be a much nicer place if the few stupid services we are able to perform for the likes of you were taken over by machinery. That wonderful Mandarax you’re scratching your ear with now: what is that but an excuse for a mean spirited egomaniac never to pay or even thank any human being with a knowledge of languages or mathematics or history or medicine or literature or ikebana or anything?” -- Kurt Vonnegut, Galapagos [8]

A whole process of deprogramming, involving new narratives, new libidinal attractors, as well as new ways of sharing knowledge, will have to be undergone. - Mark Fisher [9]

***

At the micro-level, the dispelling of the curse can occur in one of two ways.

1) Particularly in terms of cultural artifacts and narratives, dispelling the curse requires some kind of critical irrealism; a relatively untethered, unencumbered working-class imaginary. These are actions, gestures, images, narratives, artistic and otherwise, that, however quixotically, attempt to exist outside of capital’s mediations, attempt to represent the material and psychological totality of the working-class subject, and are simultaneously explicit in their hostility to capitalism. The accumulation of these fragments of images, gestures, and narratives, sets the goal of creating a counter-mythology (in the anthropological sense) to capitalist realism. This is our socialist approach to cultural production at the micro-level.

OR

2) The curse of capitalist realism can be replaced by another, darker, curse. That is, capitalist realism can be traded for the ideologies of fascism, for the primal scream of the middle-class.

At the macro-level, the curse, of course, can also be dispelled by one of two things.

1) The mass activity of the working-class itself, in effect queering and then eradicating the capitalist “Real”; i.e., the process of proletarian reform and revolution.

OR

2) The dark Sabbath of fascism; in which the limits of capitalist realism are shifted, narrowed for some, expanded for others, and re-organized through an alliance of (parts of) the bourgeoisie and a petit-bourgeois movement or constituency; usually organized and activated through a hatred of Jews and other ethnic or religious groups; with antipathy to feminism, and a concordant celebration of the abstract “family,” etc.

As André Breton argued at the midnight of the last century, referring to Nazism, we are desperately in need of a mythology to counter the “myths of Odin.”

It must be emphasized, however, that the slipstream between capitalist realism and fascism is, of course, a much quicker, and far less oppositional road, than the liberal bourgeois would have us believe. Even at the individual level, capitalist realism demands an everyday cruelty and stymied imagination that sets the table for fascism.

There was still plenty of food and fuel and so on for all the human beings on the planet, as numerous as they had become, but millions upon millions of them were starting to starve to death now. The healthiest of them could go without food for only about forty days, and then death would come. [10] - Kurt Vonnegut, Galapagos

What’s more of an issue is the kind of soft totalitarianism of neoliberal dictatorship, isn’t it? I don’t use those terms lightly. This situation where people – where there’s a rhetoric of choice and no effective political choice, where there’s a general kind of hopelessness and people feel they’ve got no control over their lives… [11] – Mark Fisher

The day after last Thanksgiving, two of our editors, Adam Turl and Tish Markley, stopped at a Denny’s in Las Vegas for dinner after Markley got off work. This was not on the Strip or downtown; this was a part of town where working people live, across from a “hospital” where working and poor people die. A couple booths away an elderly Black woman in a wheelchair nodded off while eating her dinner alone. The manager called the police and EMTs. The police arrived and forced the woman, against her will, to go to the hospital. Turl and Markley were seething but didn’t speak up. The police in Las Vegas do not have a good reputation, even compared to the other armed thugs of the capitalist state. Moreover, perhaps the woman did need medical attention.

After the elderly woman had been put into an ambulance, however, a police officer returned to the restaurant. He asked the manager if she wanted to press trespassing charges. She said yes. At this point Turl couldn’t bite his tongue any longer and demanded to know why the manager was charging an elderly disabled woman, and paying customer, for trespassing. The response was, she had done it before, and she was “abusing the privilege” of sitting in the Denny’s. Worse, Denny’s workers backed up their manager. After a few minutes of pleading on behalf of the old woman Markley and Turl left fearing that they might draw the attention of the police still milling about in the parking lot.

Art by Sambaran Das from Locust #2.

Dreams Cum Tru from the Born Again Labor Museum

Dreams Cum Tru from the Born Again Labor Museum

This is the internalized curse of capitalist realism; the neoliberalism in our souls. Every single one of us, and every single one of those Denny’s workers, could easily end up where that old woman was; alone (if only for that evening), broken, old, in a hostile world. That is the “logical” outcome of existential and class “reality” in the United States. But that simple leap of imagination was lost that evening. Our siblings only saw the moment. They were being “realistic.” This is how capitalist realism paves the way for the new fascism; for usually decent people to accept the unacceptable.

Capitalist realism was only ever a fantasy – a fantasy that the human resources capital needs for its growth were as infinite as its own drive. Yet capital is now coming up against limits of all kinds, and existential limits are not the least of these…

What happens when you demoralize people, destroy their capacity to commit to any purpose in life other than capital accumulation, and don’t even pay them? What if you don’t even offer them the possibility of being exploited, and classify them as a surplus population? [12]

The political center, in the long run, cannot hold. This is the lesson of recent politics. As capital begins to face its limits, not the least in global climate change, the illusion of never-ending capital accumulation will fail. The masses will seek new myths; good or bad.

The faltering of the center is even evident in the recent UK elections; falsely read by the mainstream as a rejection of socialism. The Labour Party failed, it seems to us, in part, precisely because it was afraid to alienate petit-bourgeois remainers; or fully confront the racist logic of many leavers. It failed to offer a radically democratic alternative to both Tory xenophobia and the neoliberal European Union. Without a clear response to this contradiction Labour’s left social-democratic manifesto seemed hollow and alien.

Hanged Books in the Born Again Labor Museum

Wounded Tool 32596-8-T - Sickles (Wounded Tool Library, Born Again Labor Museum): Like most sickles, these artifacts grew tired of harvesting crops and cutting weeds long before they were replaced by electrical and motorized tools. After misunderstanding Walt Whitman’s Leaves of Grass – a book very popular among sickles – these artifacts aspired to become poets. The sickles, however, are only capable of harvesting words from already existing poems. Before being captured by the Wounded Tool Library these sickles harvested most of the poetry in the St. Louis public library.

Wounded Tool Library, Born Again Labor Museum

Art and literature cannot stop fascism. Only masses of the exploited and oppressed, armed with a militant consciousness and organization, and often armed with actual weapons, can defeat fascism. But our art and literature will imagine the entirety of working-class life. Not just the false empirical slices that capital offers. Not the partial view that enables such cruelty. Not just the material drudgery. Imagine each of our working-class siblings as a column. Each apex pierces the cosmos. Each pedestal is, within capitalism, covered in shit, blood, and cum.

The snake-skinned bartender stood up from behind the bar. The scales on his back were standing on end exposing the baby like flesh beneath. He said, goddamnit! Did you have to clap that suck-ass in here? Look at my fucking joint! Millard heard and saw this as ..mslknoids, lksdfjlll lhjjljlj,bnldjso0. But, his asemicated mind was settling now. Everything was returning to a measure of normal and the weight of it made him instantly tired.

He smiled at the scaley barkeep and said, 888jnno j...ls]][fasdf.

(Remind me not to drink when I’m hunting fascists).

And with that he walked out into the heat. - Mike Linaweaver, Millard 19017, Fascist Hunter [13]

When I moved to America. I lived in Rockford just trying to hide from the press – you know, as they say in Rockford, nothing happens here but terrible, boring things… [14] - Mark Miller, The Librarian at the End of the World

The digital matrix, the social industry, the digital gesamtkunstwerk, is rarely boring. But it always exists in relationship, for countless working-class persons, as the bright light of mutual despair; a light surrounded by the “terrible, boring things.” For the increasingly weird working-class, irrealism has become a default cultural response to these “terrible, boring things.” As Adam Turl notes of his drawing students, when allowed to make comics of their own design, their narratives are almost always irreal.[15] They borrow heavily from speculative fiction, science fiction, fantasy, manga, comics, fan-fiction (their own and that of others), irrealist memes, etc. The fantastic becomes a tool/toy box of tropes, allegories, absurdities, that can be used to make sense of their own lives; to make sense of how their identity and unique subjectivity intersects with a seemingly disintegrating social totality.

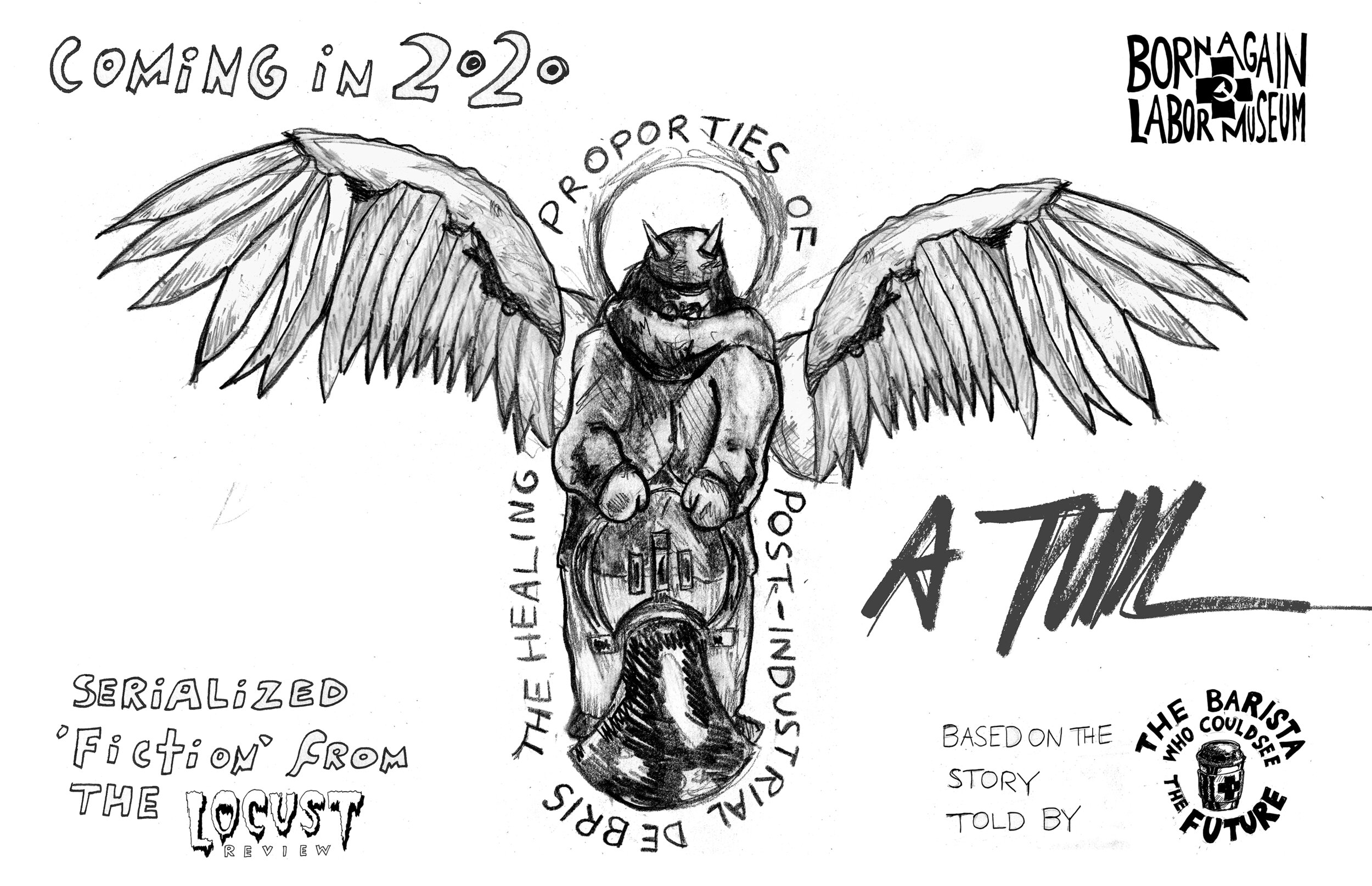

Promotional drawing from Locust Review

Promotional drawing from Locust Review

Promotional drawing from Locust Review

Of course, not all irrealism is critical. Much of it, as already noted, aspires to the dubious status of realism. It does this by echoing bourgeois morality, gritty and “Real.”

Think of the Song of Ice and Fire. For all Martin’s criticisms of power in his epic – not all that critical it seems after his endorsement of Joe Biden – his fantastic narrative offers no way out. Worse, the number of characters from outside the ruling classes of Westeros is nearly insignificant. This means there is little imaginary that flows from the serfs, slaves, and peasants (in other words, the characters that would be a stand in for the present working-class). When the middle-brow and mostly middle- and upper-class audiences pulled up their chairs to watch HBO’s adaptation they were watching something that largely confirmed their view of the world. The world is brutal. But you have to fight for yours. Of course it is better if you do it smartly. The sword of Damocles hangs over everything (war, climate change, the army of the dead). But isn’t Tyrion smart (like me!)? Half the people, or more, of King’s Landing are dead. But here’s the small council and Tyrion is Hand again! Of course there were more critical elements in Martin’s narrative – which infuriated his petit-bourgeois liberal audience. Of note here is the story arc of Daenerys Targaryen. Who would have thought a white, blonde, savior-from-above type, who liked to crucify people, would turn out to be a bad egg? After all, the liberal petit-bourgeoisie, which makes up the bulk of HBO subscribers, is full of white, blonde, savior-from-above types who like to crucify people (in one way or the other). And they are simply the best people around. They watch John Oliver. And they went to college, too.

As we note, irrealism becomes truly critical when it

emphasizes the alterity, the otherworldliness, of these styles to discover a radical truth living in the cracks of late capitalism. The surrealists might have called this the “dream image.” Indian communist artist Anupam Roy (featured in our first issue[16]) calls it “the real image.” Whatever it might be called, we see it as corresponding more closely with how people experience and interact with a world at once hyper-connected and alienated while threatened with really-existing catastrophe. [17]

In the next section we will begin to discuss what this critical irrealism might look like in the here and now.

The simplest Surrealist act consists of dashing down the street, pistol in hand, and firing blindly, as fast as you can pull the trigger, into the crowd. - André Breton [18]

There I see that the NRA is working through their proxies to ensure that bulletproof glass is found to be an unconstitutional assault on the 2nd Amendment, but Diane Feinstein, the senior Democratic Senator from California is pushing back by declaring that certain kinds of ballistic glass are protected free speech. A bipartisan group of senators has opined both aloud and in public that if you can’t shoot who you want when you want there is little point in having a well-regulated militia in the first place, and this appeal seems to be gaining traction in the south. [19] - Mark Miller, The Librarian at the End of the World

***

“Gib” from Tish Markley’s “Space Goths” on display in the Born Again Labor Museum as part of the BALM Puppet Project (2019).

BALM drawing from Locust Review #2

Linda Copbane and Mr. Week Handit in the Born Again Labor Museum

Promotional drawing from Locust Review

Tish Markley working on the Born Again Labor Museum (2019)

Promotional drawing from Locust Review

Anupam Roy

Drawing of Tish Markley for Locust Review

Reciting stories from Locust Review at the Born Again Labor Museum

Modern absurdist literature reflected contradictions between desires for value and meaning versus a chaotic and irrational social and existential condition. Neoliberalism claims to be rational. Its artifacts claim to be “real”; its reality television shows, social media performances, formal narratives, and empty conceptual art gestures. But the working-class subject experiences the rational and real as chaotic insanity. In this admixture of realistic horrors, paradoxically, it is in the absurd that the proletarian subject can begin to reimagine purpose. As we argued in our first editorial:

Our irrealism must be, at punctuated moments, absurdist. The contemporary invocation of absurdism is an assertion of tricksterism. This is a representation of how a precarious working-class experiences events as cosmic randomness: 9/11 and the “War on Terror”, the economic collapse of 2008, the rise of Trump, the vagaries of online mobs in a world in which every online person has become a public figure, the sudden growth of socialist organization in the U.S., etc. Or, more prosaically, the sudden loss of health insurance, employment, housing, a sudden death at the hands of the police, the sudden demise of a bourgeois politician caught in a pedophilia ring.

In this cosmic random variable lies hope as well as tragedy. The trickster is not good or evil. It is creation and destruction. This is not to say the aforementioned events are truly cosmic or random. They can be explained by Marxism and science. However, they are often experienced in a manner the recalls the randomness of everyday life among our hunting and gathering ancestors.[20]

Capitalist realism is increasingly unable to make sense of the world capital has made. At the same time, irrealism (of a sort) is part and parcel of the culture of capitalist realism. There is the “realistic” space opera that eschews the telltale signs of the genre’s historic artifice. We are given faux cinema verité in outer space. When we miss the less sophisticated iterations of things we are missing the human elements, the hands of the artists, the clumsy (but beautiful) interior lives of previous generations hobbled together on sound stages and studios. Total Recall (1990) vs. Total Recall (2012). Robocop (1987) vs. Robocop (2014).

While the culture gets “real,” of course, reality gets less “real”; almost living beyond what can be satirized.

“Self-driving Mercedes will be programmed to sacrifice pedestrians to save the driver”

“Thousands of penis fish appear on California beach”

“Taste the ash, see our pink sun: Sydney’s dead future is here”

“Trump team released a video of him as Thanos, the villain who commits genocide in the Avengers movies…”

“Ohio House passes ban on local bag bans”

“People in Japan are wearing exoskeletons to keep working as they age”

“US Army Worries Humanity is Biased Against Deadly Cyborg Soldiers”

RHINOCEROS! [21]

This shark must be intentionally jumped. In his book, The Librarian at the End of the World, Mark Miller shows the absolute necessity of the absurd; that the absurd is often necessary to reassert a human core. Ramdas Bingaman – secret insurance agent, librarian, porn actor, celebrity-bio-cheese thief, ex-professional speed bather – navigates all manner of things before getting to the core. Imperialism. Capitalism. Revolution. The Existential Condition. More or less, in that order.

RHINOCEROS!

But Ramdas Bingaman only arrives at that denouement after, among other things, billboards are posted of him being pegged by “Amazonian fem-doms” accompanied by the text “Ramdas Bingaman is coming for your guns!” He is offered a role in a pornographic film, possibly titled “He Wants to Raise the Minimum Wage.”

CUCK!

The far right, in Miller’s book, argues that bulletproof glass violates the second amendment. What’s the point of having a second amendment if you can’t actually shoot the people you want to shoot?

Good point.

RHINOCEROS!

Ramdas poses as the regional manager of the Bonsai Burrito fast food chain. He asks a shift manager, Jeffrey, what will happen once all the rainforest has been cut down, and all the grass is gone, and the last cow has died. Jeffrey responds, “The cessation of life on the planet?”

“It means there will be no more beef,” Ramdas corrects him. “So we need for our customers to have eaten more beef than the others, so they will be strong, loyal, and willing and able to fight. This is all coming to a head.”

RHINOCEROS!

There is another aspect to our “jump the shark” imperative; beyond the increasingly bizarre world of capitalist realism. This flows from two problems of recent left cultural production: The faltering of “socialist realism” and the insufficiency of court jesterism. Instead, we call for an overdetermined cultural socialism.

Art by Anupam Roy

Jon Cornell’s Terror Kultur from Locust #1

As we wrote in the announcement of our first issue:

Socialist Realism, in the contemporary context, tends to assume a non-existent “normal” working-class. The working-class is weird. There is no normal to appeal to. Critical irrealism assumes a working-class that contains within itself varied and queer multitudes. It assumes the gravediggers of capitalism to be a chaotic jumble. And that each individual gravedigger contains within them an entire universe. [22]

Moreover, the idea of the “normal” is related to the problem inherent to all “realisms” mentioned earlier. The lifting of the “realistic” fragment out of its greater narrative and social totality immediately cedes ground to bourgeois compartmentalization and abstraction. Even the most demographically “standard” worker is only “normal” when abstracted from their actual biography, psychology, and inner narrative. In other words, they are only “normal” when their actual subjectivity is ignored or repressed.

In this way normie socialism, and much socialist realism, performs the same kind of reduction and assault on individual working-class subjectivity as neoliberal capitalism. The working-class subject, made “weird” in part by the collapse of fordist labor, and made precarious by capital, once again loses their limited free will; but this time at the hands of vulgar Marxists and crude social democrats. This “Marxism” therefore performs in its essence another version of capitalist realism. The worker is deprived agency once again.

With the collapse of the socialist left, the defeat of much organized labor, the neoliberal turn, the rise of capitalist realism, and the mushrooming of endless critical theory, left-cultural production turned increasingly toward what we could call court jesterism. Our critiques of capital would be secretly coded in cultural products that could find expression in the spectacle. But we were often too clever by half. Much critique was so coded that it failed to criticize, became easily reified, and became tropes absorbed by bourgeois metanarratives. Indeed, the emphasis on secret coding echoed the general retreat of the class and the socialist movement.

While court jesterism sometimes produced good art – especially in pockets of speculative fiction and pulp film genres where it could be the most open – it failed spectacularly in the weak avant-garde.

“The Wounded Tool Comic” as it will appear in Locust #2.

“The Wounded Tool Comic” glitched IRL as it appears in BALM.

Here, we take the lessons from so-called “Outsider Art;” in which artists do not usually attempt to hide or secretly code their philosophical worldviews, good or bad. We take from these artists the lesson that we need an overdetermined socialism in our art. This does not mean our work should consist of hagiographic portraits of Lenin or other such nonsense – although we are not against portraits of Lenin that, say, get at the contradictory legacy of October as it relates to the socialist movement and working-class lives. Regardless, our overdetermined socialism focuses on the individual and collective agency of working-class subject(s). This includes overt political organization. It also includes dreams and nightmares, spells and curses, angels and demons, aliens and monsters, failures and libidinal impulses.

We will strive for: A democratic dreamwork; A preliminary and collective sketch that echoes Anatoly Lunacharsky’s idea of mass democratic god-building.

That is to say: Our socialist irrealist art will intentionally jump the shark.

“Most souls automatically find themselves in heaven, which turns out to be a multidimensional holy battery created to boost god’s power. Only those who specifically made pacts with demons end up in hell, which isn’t so much a place of punishment as it is just some other god’s soul battery. The Queers build cozy enclaves with warm hearths in the perpetual rain of limbo.” – Beatrix Morel’s response to the question, “Do you dream of the end of the world?” in Locust Review’s “Irrealist Worker Survey #1” (to be published in the forthcoming Locust Review #2)

***

Artistic and political strategy are related, and ideally mutually reinforcing, but should not be conflated. Because so much of art is about individual performance, gesture, psychology, dreaming, and so on, it cannot be reduced to a practical political program. Moreover, what works well as an artistic strategy may or may not work well as a political one. For example, the various “Fully Automated Luxury Gay Space Communism” memes were excellent re-assertions of the right to working-class dreams. However, when certain socialists attempted to turn those memes into actual theory and program they produced accelerationist silliness. An overly aesthetic approach to politics, or an overly utilitarian approach to art, are both mistakes we must try to avoid.

Art by James Walsh from Locust #2

Art by Adam Ray Adkins from Locust #2

Art by Leslie Lea from Locust #2.

That said, the design of both socialist artistic and political practice, at this moment, must each push beyond the illusionary limits of capitalist realism.

There is more to be said. There is the issue of time – of the gothic-futurist arrhythmia of neoliberal culture. There is the question of the digital gesamtkunstwerk (or social industry). There are the philosophical origins of socialist realism – which, as noted by the philosopher Holly Lewis, let a Cartesian dualism sneak through the back-door of cruder historical materialisms.

But for now, we should end with this. The working-class is made of actual individual human beings. The only aspects of our individual lives not yet fully commodified and reified – although the tech billionaires are trying their best – are our dreams (waking and sleeping). When we say, we are many, they are few, that is true of the dream-life of our species as well. And our proletarian dreams are better than their bourgeois nightmares – which they, with typical self-importance, consider reality.

***

“They can’t kill us if some are still sleeping in the ground. There will always be more of us in the dirt waiting to drag them down.” – Joy Happiness Gleam’s response to the question, “You are a locust. It is the night before the insurrection. Some of your fellow locusts are wavering. What do you say to steel the revolutionary ardor of the swarm?” in Locust Review’s “Irrealist Worker Survey #1” (to be published in the forthcoming Locust Review #2)

BALM drawing and digital collage from Locust #1

Anupam Roy, Brahmin Colonizer’s Apparatus, from Locust #1

Endnotes

[1] This could also be called, per Mark Fisher, “Acid Communism.” It is also closely related to the idea of salvagepunk outlined by Evan Calder Williams in Combined and Uneven Apocalypse: Luciferian Marxism (Zero Books: London, 2011)

[2] Mark Miller, The Librarian at the End of the World (Montag Press: Oakland, 2019), 107

[3] Tish Markley, “Space Goths,” Locust Review #1 (Fall 2019), 5

[4] Mark Fisher, K-Punk: The Collected and Unpublished Writings ofMark Fisher (2004-2016) (Repeater Books: London, 2018), 276

[5] John Berger, Ways of Seeing, Episode 1 (BBC: 1972): https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=0pDE4VX_9Kk

[6] Fisher, 562

[7] Fisher, 563

[8] Kurt Vonnegut, Galapagos (New York: Dial Press/Random House, 2009), 71-72

[9] Fisher, 565

[10] Kurt Vonnegut, 24

[11] Mark Fisher, 657

[12] Fisher, 614

[13] from Mike Linaweaver, “Part 1,” Millard 19017, Fascist Hunter, serialized fiction in Locust Review #1 (Fall 2019), 4

[14] Mark Miller, 69

[15] Adam Turl, “Born Again Labor Museum,” video based on a presentation from Historical Materialism London (2019), RedWedgeMagazine.com (December 3, 2019): http://www.redwedgemagazine.com/online-issue/london-balm

[16] Anupam Roy, after this was written, also became an editor at Locust Review.

[17] “Announcing Locust Review,” LocustReview.com (September 25, 2019): https://www.locustreview.com/editorial/announcing

[18] André Breton, “Second Manifesto of Surrealism,” in Manifestoes of Surrealism (Ann Arbor Paperbacks: Ann Arbor, 2010), 125

[19] Mark Miller, 106

[20] “We Demand an End to Capitalist Realism,” Locust Review 1, (Fall 2019), 2

[21] This is a reference to Eugène Ionesco’s absurdist play Rhinoceros (premiered 1959), widely seen as a parable of the rise of fascism prior to World War Two, the inhabitants of a town progressively become rhinoceroses

[22] “Announcing Locust Review,” LocustReview.com (September 25, 2019): https://www.locustreview.com/editorial/announcing

Locust Review is a publication of the radical weird, catapulting itself into the future by way of the past. Published in anachronistic newspaper format four times a year and online, we are unapologetically socialist, experimental and irrealist in outlook, clinging to the hope of discovering a profane illumination out of the end times. It is a joint publication of the Locust Arts and Letters Collective (LALC) and the Born Again Labor Museum (BALM). Locust Review is edited by Alexander Billet, Holly Lewis, Mike Linaweaver, Tish Markley, Anupam Roy, and Adam Turl.