Michelle Cruz Gonzales (then known as Todd) played drums and wrote lyrics in Spitboy, one of the most important hardcore bands of the 1990s. Along with bands such as Grimple, Econochrist, and Paxton Quigley they were part of an explicitly political corner of the East Bay punk scene. With an all woman line-up Spitboy’s performances defied expectations of what “women and rock” and “feminism” were supposed to mean at the time. Gonzales’ new book Spitboy Rule: Tales of a Xicana in a Female Punk Band (PM Press) defies expectations once again. People of Color have been part of the punk scene from the beginning. Gonzales is part of a lineage that includes Detroit’s Death, The Bags (Los Angeles), Poly Styrene and Pat Smear. Spitboy Rule makes the invisible visible. It is both a walk down counter culture’s memory lane as well as a serious exploration of identity, gender and race.

* * *

James Tracy: Numerous books and articles have depicted the 1990s as revolution (of sorts) for women in rock and punk. What stories are left out of this version of history?

Michelle Cruz Gonzales: Yes, Kim Gordon of Sonic Youth and Carrie Brownstein of Sleater Kinney, and most recently Michelle Leon of Babes in Toyland, have all written books on the subject, and there are several books about riot grrrl. While Gordon and Leon predate riot grrrl, much of the [discussion of] 1990’s “women in rock” focuses on it. This does two things poorly: it fails to clarify that not all women in music were riot grrrls, and it fails to fully see, acknowledge or make visible women of color.

After a reading a Q&A session I did with Alice Bag, Michael T. Fournier, and Keith Morris, Alice told me that after The Bags, as she continued to play music with various latinas rockeras, even she was asked in interviews if she was a riot grrrl! Can you believe the nerve of someone asking Alice Bag, who was in a seminal punk band from the LA scene in the late 1970’s, if she was a riot grrrl? Sadly, I think that the question had to do less with nerve and more to do with ignorance.

I wasn’t worried about Spitboy’s (also not a riot grrrl band) story being left out of this version of history as I began writing the pieces and put out the ‘zine (a pre-curser to the book), but after I got a book deal with PM Press, Gordon’s book came out, then Brownstein’s, and on quite big presses. I then began to worry. At first, I just wanted to document the band and my experience in it; to offer another perspective, the perspective of a person of color. But Gordon and Brownstein’s books coming out made me realize that I had a responsibility to clearly represent Spitboy; not as a riot grrrl band, to show there was an alternative, and to illustrate what it was like being a person of color, or a Xicana, in the Bay Area punk scene in the 1990’s.

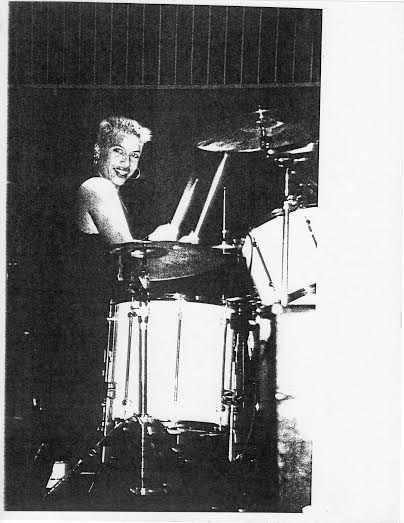

Spitboy, European tour (1993)

JT: In your book you write about some of the tensions that arose between Spitboy and parts of the riot grrrl movement. Looking back were these issues that critical?

MCG: Yes, they were critical because if you don’t define yourself, others will define you, and that takes away power. It was also critical to be clear that, while we supported riot grrrl and believed in just about everything they did, we just didn’t want to be packaged that way.

JT: You write powerfully about racism and misogyny in the world of Punk and Hardcore. How do the dynamics most punks claim to hate show up in the scene?

MCG: One reason I think those dynamics show up, or showed up, in the Bay Area scene was because the Bay Area has always been home to wealthy, educated, privileged folks, and they and/or their offspring feel they are educated on all the issues. This causes some to be arrogant to their own obliviousness. A “we-live-in-Oakland/Berkeley-we-understand-protest-issues” attitude can make people oblivious to seemingly smaller offenses, things like the 1990s approach to race, which was colorblindness.

In her amazing preface for my book Mimi Thi Nguyen points out how in the 1990s punks were super anti-fascist but only in a sort of abstract way, not quite realizing saying things like “You’re Mexican? You’re like the whitest Mexican I know” was invisiblizing. One of my old roommates in the punk house where I lived in West Oakland once said, “We’re all white here,” and I was like, “Um, what? We are?” It was like she hadn’t even noticed that I wasn’t. Because we were all part of the punk scene, I just got lumped in with everyone else. At first I sort of liked this because it meant I fit in, but it didn’t match up with how I saw myself at all.

JT: Is today's Punk scene a better place for working class women of color? In what ways has it evolved? In what ways has it stayed the same?

MCG: Since I don’t go to shows, and since I’m no longer a working class woman of color, it’s difficult to answer that question. I know that sounds weird, but it’s important for me to acknowledge that I may have blind spots too due to the level of privilege and financial security that a position as a college faculty member gives me. I know I earned all of these things, but I also know I am lucky too. Still, I wouldn’t want to speak for working class women of color in the scene today. I did, however, ask some to respond to this question via my Spitboy Rule Facebook page, and here’s what I learned:

Cristina Calle says, “In the NW/Seattle area I see a lot more women (of various ages & races) at show now then I ever have.”

Mariam Bastani, coordinator of Maximum Rock and Roll and singer for Permanent Ruin says, “Punk and HC is/always has been and always will be mostly youth oriented, so lots of kids weren't necessarily working unless they had families they had to help support or ifr they didn't have family. To assume that punk WASN'T a good place for these types of people is presumptuous, also it has a lot to do with WHERE in the U.S. we are talking about. Also, you gotta ask, is the WORLD a ‘better’ place for working class POC women? Fuck no. It’s not; punk doesn’t exist in a vacuum, so it’s not either but at least punk has always been a space where larger issues can be discussed. That doesn't mean the discussions are good, hahah, but it's not taboo like it is in norm society.”

Susana Sepulveda (aka Susy Riot) from Las Sangronas y el Carbrone and a Gender and Women's Studies grad student at the University of Arizona says, “There seems to be more spaces being created by and for women of color in punk that are strongly tied to activism and social movements that do community outreach and organizing. But in my experience, outside of these spaces, there is still a struggle to reclaim your space in punk, especially as a woman of color.”

JT: Depending on who you ask, punk is somewhere between 40 and 50 years old. Is it still relevant?

MCG: It is still relevant to me, and I think it remains relevant to others because it’s a subculture that combines art (music, ‘zines, books, crafts) and ideas. It is also relevant to me all over again at this age, at this stage of human development, as a 46 year-old woman in the early stages of menopause. I wrote about this, but it’s worth repeating. Perimenopausal women are sick of taking everyone’s shit, and those of us who came up in punk rock can fall back on it to get us through.

Michelle Cruz Gonzales played drums and wrote lyrics for three bands during the 1980s and 1990s: Bitch Fight, Spitboy, and Instant Girl. In 2001 and 2003, she earned degrees in English/creative writing from Mills College, where she also minored in ethnic studies. Michelle has published in anthologies, literary journals, and Hip Mama magazine. She teaches English and creative writing at Las Positas College. She’s at work on a satirical novel about forced intermarriage between whites and Mexicans for the purpose of creating a race of beautiful, hardworking people. She lives with her husband, son, and their three Mexican dogs in Oakland, California.

James Tracy is co-author of Hillbilly Nationalists, Urban Race Rebels, and Black Power (Melville House Press). He has edited two activist handbooks for Manic D Press: The Civil Disobedience Handbook and The Military Draft Handbook. His articles have appeared in Left Turn, Race Poverty and the Environment, and Contemporary Justice Review.