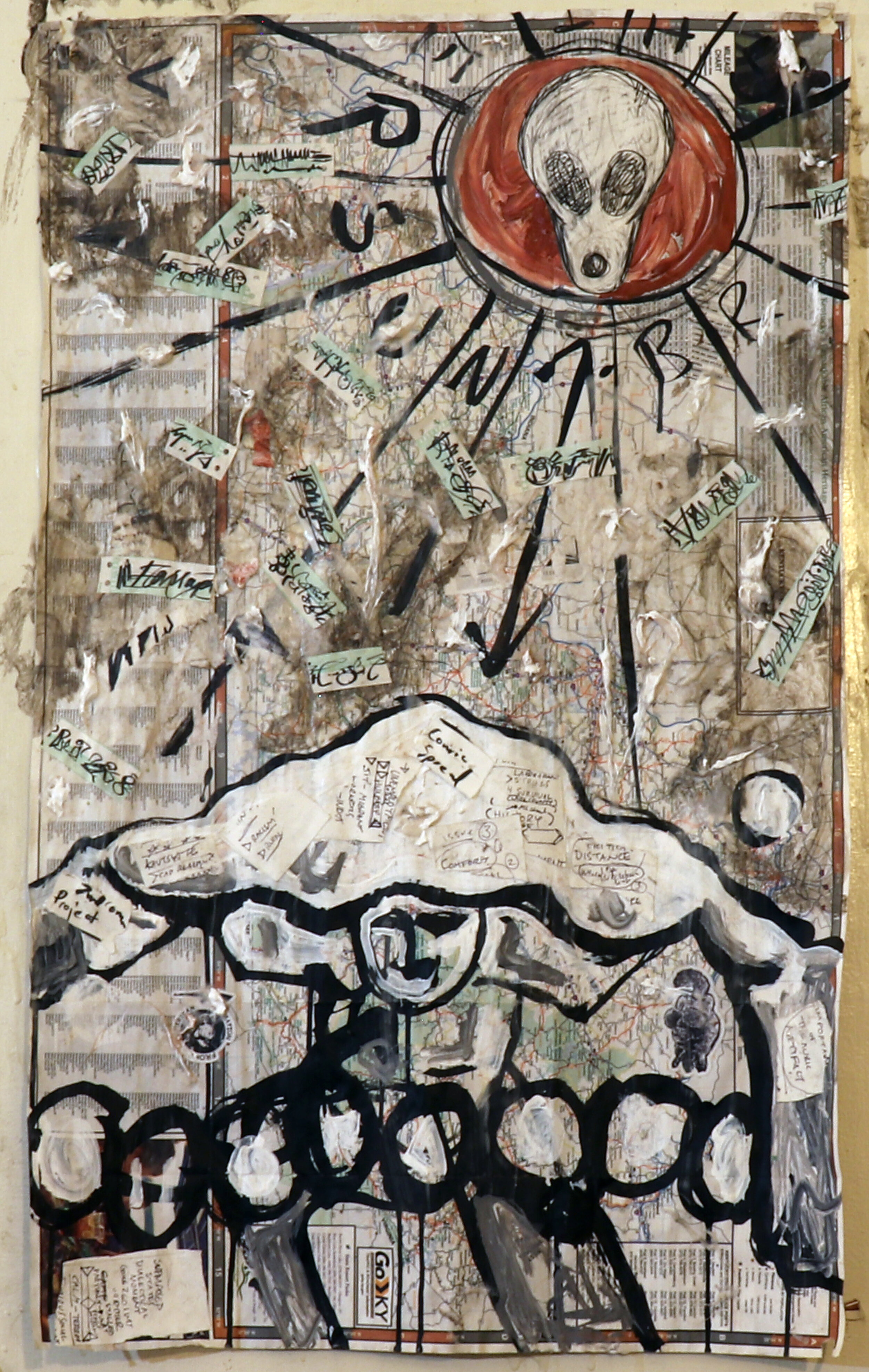

Alien Sky from the Born Again Labor Museum; acrylic, ink, collage, coffee, cotton and ash on a map of Kentucky (2020).

We are beset on all sides by disturbances of what the ancient poet-philosopher Lucretius called “an alien sky.” The Covid-19 pandemic is felt by all of us as a presence, a presence of that which should not, which cannot be—inasmuch as our ordinary perceptions define what can and cannot be. It sticks out like a sore, a wound, sudden and without warning causing even the bravest and strongest to groan. Our lives were moving right along, certainly already beset by intrusions into a billion little homeostases, when suddenly it all came crashing down. Before horror, we have felt a fascination with the very strangeness of it all, this thing which should not be that has arrived on our doorstep.

This leads to the second experience, of absence. This is a peculiar absence, not of the eerie scenes of cities depopulated by stay at home orders which, after all, have rational explanations, but a distinct absence of agency. Viruses are not, strictly speaking, living. Biologically inert, they do not perform metabolic functions, reproduce, respond to stimuli, nor do they conform to the cellular model of life. They are merely particles of genetic material in a casing (in the case of the novel coronavirus at least). They cannot be cultivated in a petri dish. They happen along, by circumstance, until they find host cells to hijack in a purely passive process.

Who then is responsible? Certainly there are responsible parties for our response to an emerging pandemic, but that is not what is of concern here. The tendency is to evade this anxiety of the eerie absence of agency. Conspiracy theorists blame a shadowy cabal (usually Jewish or Chinese) running global affairs. “They” plan to roll out a harmful new telecommunications technology. “They” plan to bring down a far right President or two. “They” plan to sneak socialism into our lives through a media-induced panic. “They” plan.

But nobody planned the pandemic. Nature is not “thinning the herd,” because “Nature” strictly speaking does not exist—at least not in the sense of an agent, an author, or an autocrat dispensing decrees. Nature is nothing but the sum of natural processes characterized by emergent forms of organization and change, not an all-seeing Sovereign. Nature is the accumulation of the small.

The world is stranger than we imagined. Above our heads we wonder at the vastness of the cosmos, the infinite stars in the night sky, the endless expanse forming into strange galactic structures. But this awe, while not misplaced, ignores the more immediate cosmos, the microcosmos beneath us. Our “selves” are the product of the evolution of organisms over centuries, now transformed by the incredible adaptations of language and culture, but nonetheless a highly tuned series of mechanisms which extend towards the infinitesimal. Billions of lives—bacteria, cells, organelles—work together in a symphony to make each and every one of us.

Human cultures have long been presided over by strong men who desire, above all else, to have the small and weak extol them for their largeness. Thus, the divine is the large, the ambitious, the massive. The greatest monsters are giants that roam the land. But lurking just beneath the surface, subterranean powers emerge to remind these big men again and again that they are not so special. Emperors fall to plague just as readily as peasants. The greatest abundance of terrors and wonders can be found not towering over us as a grotesquery of megafauna, but lurking inside us governed by simple mechanical logics. The greatest threat to absolute monarchs turned out not to be the monarchs next door, but the paupers forced to grovel at their feet.

And so we are reminded once again by this pandemic that the cosmos is a vast place not only extensively, but intensively in the form of viruses and particles. We experience it as the weird, as the sense of wrongness that makes us feel as if this thing should not exist—or at least, not here, in this time, in this age, in the year 2020. But the object is here, so it is our categories, our conceptions, which are in need of revision.

But this is not all, for the other side of this is the eerie. The absence of an agency governing our very lives at this moment. There is none from whom to seek redress. There is no there, there. Our situation is the very opposite of some tragic fate in which every action is imbued with meaning by an author, every death serving a purpose and following a formula. It is an entirely natural thing whose meaning can only be imposed by us.

Perhaps this is captured best in the 2011 film Contagion, a sobering example of a kind of documentary naturalism combined with the powerful unnaturalness of montage. We search the film for a protagonist in vain, the closest we come to a candidate is the sense that the full ensemble—a stand-in for humanity itself—is the protagonist, but one ever reacting to events hitting it from the outside as an alien invasion. In the film, Dr. Erin Mears (Kate Winslet), is unceremoniously killed off with a rapid and violent cut after previously appearing as a kind of hero-expert. There is no buildup, no lesson to be learned—simply a sudden death brought on by an “alien sky.”

It is fitting the Lucretius ended his great work On the Nature of Things with an account of a pandemic. The Epicurean philosophy he espoused has long been the target of the representatives of strong men for whom the idea that the cosmos is built from the bottom up rather than imposed from the top down constitutes an existential threat. In brief, it argues that things like reason and order are not acts of Providence but emergent processes. Inherent to this philosophy is the necessity of critique if we are ever to arrive at truth, because the condition of existing as an organized self carries with it a bias towards that state of organization: we assume it was always thus, or at least that everything else is just like us.

But the cosmos are strange because we are small, too. The only agency to be had is our own. The only strangeness that exists is that peculiar creatures such as ourselves find our very home strange. We have to grow up, as the Epicureans called on humanity to do so many centuries ago. We have to accept that there are no gods to save us, only ourselves. There is no do-over, only this life. This pandemic may seem strange and it might be unsettling that there is no shadowy enemy who has engineered a bioweapon to attack us, nor a Providence punishing us—but this is only the beginning of wisdom, not its realization.

We are all in this. Every single individual human self across this planet is now embroiled in this, and it is not going away soon. It has completely upended the normal flow of things. Old ways of being and organizing ourselves have to change, and the only authors of that change are ourselves. We have to begin to think of ourselves as a species. As a whole for whom every individual matters. We are only as strong as our weakest link. Pandemics do not respect borders or race or ability or healthif one of us is sick, we are all potentially sick.

--the concepts of the weird and the eerie defined here come from Mark Fisher’s book The Weird and the Eerie, 2016, Repeater Books

Jase Short is a writer and activist studying philosophy at the New School For Social Research. Their most recent writings for Red Wedge are “The Formless Monstrosity: Recent Trends in Horror” and “Virus as Crisis/Crisis as Virus.”