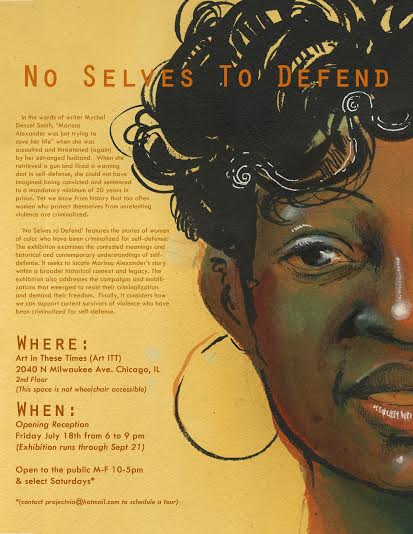

On July 18, an exhibition called “No Selves to Defend” opened in the Art In These Times space in Chicago. The opening was a fundraiser for the legal defense fund for Marissa Alexander, a Florida woman facing up to 60 years in prison for firing a warning shot in the air when her abusive ex-husband threatened her and her young children. Ashley Bohrer talked with one of the exhibit’s curators, Mariame Kaba, who organizes with the Chicago Alliance to Free Marissa Alexander and runs Project NIA, a grassroots organization with a vision to end youth incarceration.

* * *

Ashley Bohrer: How did the idea for this exhibition emerge?

Mariame Kaba: Four months ago, I decided to do an anthology project around the concept of “No Selves to Defend,” an idea that I’ve been writing on and off about for the past few years, but have been thinking about for much longer. In the context of Marissa Alexander’s case, for which I’ve been doing advocacy and support, we wanted to find a way to raise money and educate the public around women who were criminalized for defending themselves. I reached out to friends who were artists and writers to contribute to creating an anthology that would put Marissa Alexander’s case in a historical context of women who have been criminalized for defending themselves. The idea was to have a portrait of each woman and a description of her case. We completed the anthology in 6 weeks and put it up for sale in our Free Marissa online store. And we thought that one of the ways to expand the project was to do an exhibition, pairing the portraits with ephemera and historical pieces including vintage photographs, pamphlets and fliers from defense committees in the past. The ephemera and artifacts come from my personal collection. The exhibit came out of the anthology project.

AB: What has the response been like to the anthology and to the exhibit? Have people been responsive and receptive to the work that you’ve been doing?

MK: The response has been really overwhelming. People were very excited that the anthology project was happening. When we put out a preview piece, it was widely circulated on social media. We made a limited number of 125 copies and we sold out of them in a very short time. People were very interested in trying to understand and learn more about women who have been criminalized. Some of the names – Joan Little, Inez Garcia for example – might have been familiar to folks, but others are more obscure to people. Bernadette Powell and Cassandra Peten were not household names. I think people are interested in this history and in supporting Marissa Alexander’s case. It’s been a really great response, a wonderful turn out to the opening and I’m very pleased about how people have been responding to it.

AB: Why do you think there’s been so much positive response to this project at this moment in time? Do you think there’s something about the discussions and debates in the left or in the broader public that are contributing to this response?

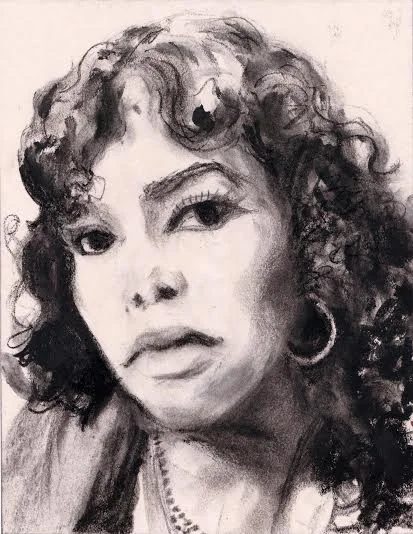

Inez Garcia” by Bianca Diaz

MK: I’m still unclear if the broader public cares very much. In the left, we are in a moment of thinking about the idea of mass incarceration and hyper-incarceration. In the last five years, more people have come on to this idea. And people have become more interested in prisons more generally. Some have even called the struggle around prisons to be a new civil rights movement, though I’m not sure I would call it that. This project and this exhibition were working to illuminate the logics of incarceration and how they structure our lives in various ways. And we’re in a moment right now when there is a greater ability to reflect on these issues than there has been in the past. But in the rise in consciousness around mass incarceration, one of the things that’s been missing has been a conversation about gender, whether that means transfolks or LGB folks or women-identified folks. Many of the conversations have been dominated by talking about men of color because they have been caught up in the system in such high numbers. But wherever there is the possibility to deepen and complicate that story, people have been interested and wanting to engage with it. This project has been a part of that.

AB: Could you talk a bit more about the title of this project — “No Selves to Defend”? What is distinctive about the way the system of mass incarceration targets women-identified people?

MK: We are dealing with mass criminalization and mass incarceration is only part of mass criminalization. We have to look at how the police target various peoples, communities, and bodies. We have to look at the ways in which hospitals, social services, the punitive nature of criminalizing poverty, and how other structures are implicated. We’ve been seeing, for example, more stories of women who have been criminalized for leaving their children alone during the day because they have no childcare. When we think about prison, we usually think about men; we usually think about black men. And that makes sense because they are disproportionately targeted by the system, but we should also think about black women. I looked at numbers of people admitted to US prisons in 1904. I had a copy of a report that I found at a library used book sale. And I looked and saw that at that time, almost 150,000 people were sent to prison that year. Out of that, 136,000 are men and 13,000 are women. The interesting thing to consider when you look at those numbers is that black women are disproportionately incarcerated even compared to black men. And this trend continues for a while. About 15% of incarcerated men are black or called ‘Negro’ at the time, but 21% of women incarcerated were black.

It’s always been the case that black women have been de-gendered within the system. It’s why discussions of black transwomen, no matter how you identified whether you saw yourself born as a woman, you were not treated as a woman. For white women, prison was very much a last resort and they were more likely to go to a reformatory. But those who were sent to custodial institutions, where black women were sent, were subjected to all kinds of abuse, sexual and otherwise. White women were always seen as redeemable, even though some of the ones who transgressed were punished harshly. Black women are still fighting to be seen as ‘legitimate’ women. They have historically not being able to claim access to being women and are still fighting to be seen as such.

The other thing to consider is that black women are black. To this day, black people are fighting to claim their humanity. We are seen as inhuman and disposable. And so when that is the cultural script around you, this leads to disproportionate treatment and makes it very difficult to claim that certain things like rights and resources rightfully belong to you. And when you’re seen as unhuman, it is hard to claim the status of corporality, being a body, and being a person. This is part of the struggle, learning how to combat and remedy that perception and therefore the treatment that you receive. That’s part of what the conversation is about. That’s what it means to have “no self to defend.”

“Yvonne Wanrow” by Ariel Springfield

In a broader way, when we talk about social locations, women are subjected to particular kinds of violence within prison that some men can escape. I’m not talking here about sexual violence, as men are also subjected to this as well. People who identify as women, broadly speaking, or who can become pregnant, are subjected to things like shackling during childbirth. Not something that men are subjected to. The way the carceral state operates is around the gender binary, so I speak with that understanding. Women giving birth are shackled. We also have to talk about the effects on families and communities when women who are primary caregivers – and many women are, as this is still how society is structured – are taken out of the household. This is hugely devastating. It is for men too but in a different way. It is important to think about those kinds of things in relation to the targeting of certain bodies and their differential experiences.

AB: At the opening reception for “No Selves to Defend”, there was a photo booth in the back room, inviting attendees to take photographs holding signs that said “Prison is not Feminist.” How do you envision this slogan being a part of the exhibit and about the message around mass criminalization?

MK: Prisons are not feminist. There was a time when feminists were not just involved in the conversation but were in the lead of prison abolition. That happened in the 1960s and 1970s. If you look at articles in Off Our Backs,Through the Looking Glass, and other publications, you saw feminists wrestling with questions about justice and police brutality and the need for prisons to come to an end. It was always contested, but in the 80s the anti-violence movement went 100% into being partners with the state and the gatekeepers of the state, the police. This happened because of funding considerations and the fact that liberal feminists believe in using the courts and the police to deal with violence against women and girls. They think it’s not only viable but desirable. They think that the police should be more responsive to claims of violence. This engendered the rise of ‘carceral feminism’. Carceral feminism is ascendent in many ways in the feminist movement because the real estate on anti-violence work was too limiting. They are now doing a lot of stuff on trafficking, conflating trafficking, sex work, and prostitution. And it is definitely about arresting people. Sometimes it’s about arresting johns, or pimps, or even the people who trade sex themselves.

At the exhibition opening, I wanted to say very clearly: prison is not feminist. When I think about feminism, I think that it means that we all deserve to live self determining free lives, free from exploitation, transphobia, violence, racism and oppression. We deserve those things. And prison is the opposite of that.

Prisons are constitutive of violence in and of themselves. They cannot be reformed and therefore prisons cannot be feminist. We wanted to make that explicit. Some of the very laws that carceral feminists are pushing have boomeranged onto the survivors of violence who are being swept up into prison based on these laws. The collaboration between the anti-violence movement gave the state legitimacy and allowed it to co-opt some of our ideas to grow a prison nation. We have to provide our own solutions that would be more in line with feminism. We cannot continue to feed the machinery of this rapacious, horrifyingly destructive system of incarceration. That’s part of what the intervention was about.

We also started Prisonisnotfeminist.tumblr.com so people can keep adding to this project beyond the exhibition. We encourage others to start posting their images with this slogan to get these ideas in peoples’ heads, especially to those who feel they are feminists or who identify with that word.

AB: What do you think is the role of art in the fights to end criminalization, racism, and incarceration? How can we think about the relationship between art and social justice activism?

MK: I wrestle with this a lot. A friend of mine invited me to be part of a conversation that they’re curating this fall at SAIC, where they are trying to have conversations about whether or not social justice and art go together. And as I was thinking about it, I started to think about all of the different kinds of art interventions Project NIA has been involved with over the past five years. I didn’t even realize how often we rely on art to illuminate ideas and impact changes in policy, structures, and culture. I think art offers the opportunity for people to think in a different way about issues. If you see something visually stimulating, it allows you to have your imagination activated in a way that words do differently. I think both are important and married together can be impactful. I also think that art hits us emotionally in a way that other things can’t. Art can also reach across differences in a unique way. I’m interested, as an organizer, in trying to find ways to connect with people where they are, to engage them in their communities, to engage them in their interests. And a lot of people are interested in art in its various iterations. It’s been organic for us at Project NIA. And it’s something that I did as a very young organizer in high school, using films and art and storytelling to talk about racism, to discuss issues with youth. It helps people to be able to unleash their emotions and to imagine something very different than the world we live in. For me, I’ve also seen art be a platform to be able to have difficult conversations and for people to feel less threatened, to be able to open up these dialogue and conversations about difficult issues.

I should also say: art doesn’t replace grassroots organizing or advocacy on the ground, but art is often used in the service of social transformation. I have a lot of friends who are artists. I like artists. My friends who are artists are more able to access certain parts of their psyche to imagine something different. What we need desperately right now is people with imagination to think about something different and who aren’t afraid to go there.

AB: Has Marissa Alexander seen the anthology?

MK: We sent her a copy of the anthology. I haven’t heard back from her yet. Her mother, who is very active in Free Marissa Now, has thanked us for this work and the Chicago-based organizing around her case. I won’t speak for her, but this project responded to something that Marissa said. She’s been asking the national mobilization committee to highlight the fact that her case is not singular, that she is not the exception, that rather, many women have been criminalized for defending themselves. Marissa has always said that she wants other peoples’ stories to be lifted up by hers. Part of our work has been to raise other women’s stories too. The idea for the anthology came from hearing Marissa’s mother and through her Marissa saying that she doesn’t want this campaign to be just about her, but to place her story within a historical context. I think for that reason she’d be pleased about what we’re doing.

AB: What else is the Chicago Alliance to Free Marissa Alexander doing right now? Are there other events on the horizon?

MK: We just got done with a month of solidarity events. We did a teach-in, the opening, the next day we screened “Crime After Crime” and then we had a large community gathering with artists and performers. We also co-hosted an event about breast-feeding and incarceration in late June. Marissa’s trial was supposed to start on Monday (July 28), but it has since been moved to December 8. There will be an event co-sponsored by CAFMA focused on anti-prison organizing and anti-violence organizing on October 16 at DePaul University. Dr. Emily Thuma who is a professor at UC Irvine wrote her dissertation on the history of the anti-violence against women’s movement and its intersection with the anti-prison movement. The title for her talk is “Lessons in Self- Defense: Women’s Prisons, Gendered Violence and Anti-Racist feminisms in the 1970s and 80s.” I’ll be speaking at that event as well. We’re also currently discussing solidarity events in the lead up to Marissa’s new trial date, which is December 8.

“Dessie Woods” by Rachel Galindo

AB: How can people support the Campaign to Free Marissa Alexander (CAFMA) and Project NIA? How can they support a project of ending mass criminalization?

MK: They can follow Project NIA and CAFMA on Facebook so they can keep track of upcoming events. CAFMA meets on the last tuesday of every month. They can visit ChicagoFreeMarissa.wordpress.com to find out when meetings are. The best way to connect with CAFMA is to come to those meetings and we operate through collaboration. People can also donate to Marissa’s defense fund. We have a Free Marissa store (link) where they can buy things. We’re also accepting donations from artists so they can be sold and all the proceeds go to Marissa’s defense. Our work at Project NIA is different. We have a Prison Industrial Complex (PIC) teaching collective that hosts a PIC 101 training that folks can attend. We also have a project called Girl Talk led by a collective of young women who go into the jail once a month who do art projects with young women on the inside. We’re about to launch a books to youth in prison project where we’ll be sending books to the Department of Juvenile Justice. There will be a call for participation. Follow us on Facebook and keep track of our blog.

Lastly, I would also say that people should keep in mind the importance of not contributing to more prisoners, of not contributing to more criminalization. Think about why you are calling the police. Even if you can’t be involved in doing advocacy, think about in your life personally how you can not contribute to criminalization. If you’re not calling the cops, if you’re watching them, if you can make sure not to contribute to the machinery of the prison industrial complex and mass criminalization, that’s also very important.

“No Selves to Defend” is on display in the Art in These Times space, located at 2047 N. Milwaukee Avenue in Chicago. The gallery is open to visitors between the hours of 10am and 5pm, Monday through Friday until September 21, 2014. If you want to attend on a Saturday or would like a group tour, contact Mariame at projectnia@hotmail.com.

Mariame Kaba is the founding director of Project NIA. She has been active in the anti-violence against women and girls movement since 1989.

Ashley Bohrer is a feminist and PhD candidate at DePaul University.