Today’s generation is raised under a dark shadow of intellectual pessimism. To be sure, it is a pessimism entirely justified by the entire experience of the 20th century as well as the 21st century up to now. But the function of a revolutionary in this is to fight, to rekindle the socialist imaginary, not because the outlook is good but because there is no other option. Our choices are to resist or be consumed. Revolt can be a joyous festival, a celebration of a future yet to be birthed. This is what Vladimir Mayakovsky[i] meant when he said, well before he shot himself, that “joy must be ripped from the days yet to come.”

Read moreThere is something rotten in Hollywood. If anything has been proven by the events and revelations of the past few months, it is that. It is also clear that the rot goes far deeper than Harvey Weinstein. Though he is clearly the worst kind of predatory slime. Or any collection of creepy, entitled individuals with a measure of power. It is a culture in which abuse is not just accepted but often rewarded, or at the very least invites no consequence.

Read moreEducational institutions are sites of struggle. Sometimes openly, sometimes hidden under layers of bureaucracy, but always consequential. Last week, lecturers at 64 UK universities walked off the job to prevent their pensions being gutted. On the other side of the Atlantic, public school teachers in every one of the 55 counties in West Virginia also went on strike. It is illegal in the state for public employees to strike at all, and yet the teachers have already appear to have wrenched concessions from the putrid opportunist of a governor, Jim Justice.

Read moreThe English translation of Richard Wright’s address to the Revolutionary Democratic Assembly in Paris in December 1948 seems to have escaped the notice of the biographers and literary scholars who have otherwise been extremely thorough in documenting the author’s life and work. And that neglect is all the more remarkable given the speech’s substance. A major defense of radical political and cultural principles at a moment when the Cold War was turning downright arctic, it is also a credo, a statement of personal values, by the preeminent African-American literary artist of his era.

Read moreHugh Masekela was one of the last great jazz men of the twentieth century. Both his life and music were shaped by transatlantic political and cultural currents that ebbed their way through the slums of Johannesburg and the jazz dives of Harlem. His death has produced two broad depictions of the man: Masekela the founder of the South African Jazz sound, and Masekela the activist who used music to raise attention to the injustices of apartheid. Neither of these are inaccurate, but they do little to capture the complexity of the man or his music.

Read moreWhen I heard that The Fall’s frontman (and only consistent band member) Mark E. Smith had died, I didn’t even realize The Fall released a new album in 2017. I consider myself a pretty good fan, I can name a bunch of their albums, know some of their songs inside and out, have read dozens of interviews and articles about the Fall – and yet it totally slipped my radar they had a new album. But to be honest, Smith just got too much for me and after album after album, just got a bit burnt out by how their sound would have that similar weird feel, but just wasn’t as amazing as it could be.

Read moreI had a friend who as a child wrote to Ursula Le Guin. He was feeling miserable, bad things had happened to him and he wanted to run away to Earthsea. He told her that he felt ashamed that he wasn’t facing up to life, felt it was a failing that he just wanted to live a fantasy. Ursula Le Guin wrote back, sending him a postcard. She told him that imagination and fantasy weren’t something to be ashamed of, they were what made us who we are. My friend kept that postcard with him wherever he went.

Read moreTo regard the struggle, the pain of a revolution, is not to deny the magnificence and optimism embodied in it. In order to fully look to the future, we have to reckon with the immensity of creating it. And acknowledge that we may fail.

Victor Serge knew this. He supported the Bolshevik Revolution enthusiastically, but as he saw its direction thrown off by civil war and rising bureaucracy, he had little hesitation in dissenting while remaining in absolute solidarity.

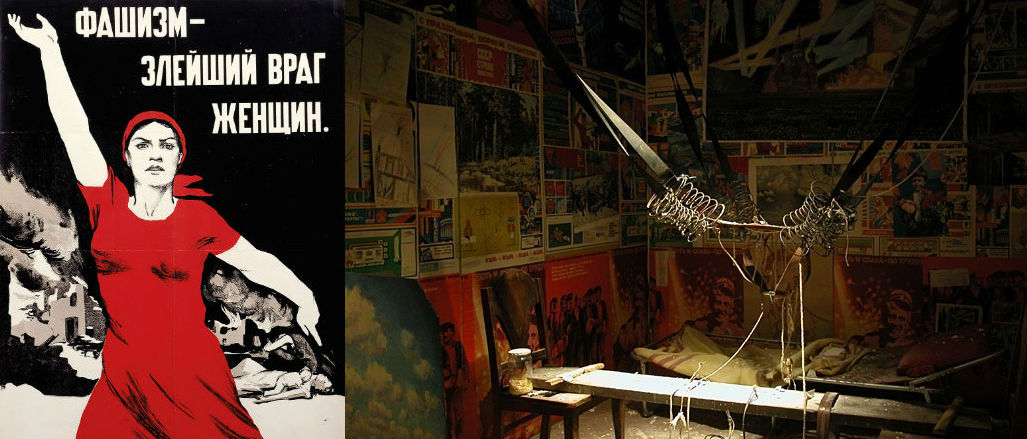

Read moreThe installation Long Live the New! Morris & Co. Hand Printed Wallpapers and K. Malevich’s Suprematism, Thirty Four Drawings, including covers, addendum and afterword is made from a combination of two books: a Morris & Co. wood block printed wallpaper pattern book from the 1970s containing 45 sample wallpaper designs by William Morris, the 19th Century English wallpaper, textile and book designer, poet, novelist and Communist; and the Russian artist and pioneer of abstraction Kazimir Malevich’s Suprematism, Thirty Four Drawings, published in 1920.

Read moreWe are born. It should be a start, but it is in fact a non-start; for we almost immediately have our full agency and autonomy as human beings robbed from us. We spend a lifetime trying to grasp it back from beneath a growing pile of rubble.

Rubble is literally at the center of Ilya Kabakov’s Labyrinth (My Mother’s Album). A large installation among many included in the Tate Modern’s exhibition of Ilya and Emilia Kabakov’s work, it is a spiral of long hallways reminiscent of Soviet era communal apartment buildings.

Read moreSome things, once said, can't ever be unsaid.

Some spells, once chanted, cannot be unmade,

but spark, leap over silicon barricades,

cast afterimages of brilliant red.

The spell creates the wizard. There lies he,

babe rocked by engines, watched through robot eyes,

his cradle hung from cables to the sky,

lulled fast asleep by steam trains to the sea.

Read moreAt 9:40pm on October 25th, the forecastle gun of the battleship Aurora fired an ear-shattering round into the air. It was a blank, an empty shell. One-year prior, the Aurora had been contributing to the carnage of World War I, patrolling and bombarding in service to the Russian Empire. Now it was docked in Petrograd and under the control of a revolutionary sailors’ committee, most of whom supported the Bolsheviks. The blank round was, so the story goes, the first shot in the October Revolution, which overthrew the Provisional Government and established the first workers’ state in history.

Read moreWhat is the relationship between artistic movements and the historical periods during which they first appeared? Can the methods associated with these movements be detached from their original context for the benefit of later artists? Do the answers to these questions depend on which movements and periods we are discussing? The issue is of more than academic interest. Serious contemporary artists want to produce work relevant to, and critical of the societies in which they live; but in doing so, are they free to draw on any methods, from any point in history, or will only some be adequate to their needs? Should socialists expect them only to work with particular methods, and criticise them when they do not?

Read morea cap of night

cold and icy swept by tangles of wire

and rickets

the unsettled courses the many empty hands

of the workers leaving empty factories

forever

Read more“Leveler” was coined in the 17th century to describe those who tore down hedges in the Enclosure Act Riots. It was later generalized. As long as the working-classes have sought political and economic leveling these aspirations have been expressed in art and culture – from the social gospel of Matthew to the gestures of punk and early Hip Hop. Aesthetic leveling can be used in ways that divert class anger toward the wrong targets or toward personalized solutions. But it also can express movement toward proletarian consciousness. And the socially promiscuous artist – coming from, and historically mixing with, all classes – is often predisposed toward leveling (as well as a political volatility that produces the aforementioned variations).

Read more“No one today can reasonably doubt the existence or the power of the spectacle; on the contrary, one might doubt whether it is reasonable to add anything on a question which experience has already settled in such draconian fashion.” – Guy Debord, Comments on the Society of the Spectacle, 1989

Within five years of writing these lines, Guy Debord – author, filmmaker, and leader of a coterie of radical intellectuals known as the Situationist International – despairing at the ever quickening advance of the society he opposed, brought his own life to an end. He had lived long enough to see the collapse of the bipolar world order of the Cold War and the Americanization of the world.

Read moreThere are different methods of celebrating an anniversary. There is that which looks back with pure nostalgia; a soft, uncritical reification that half expects time to repeat itself. It is safe to say that the vast majority of anniversaries are celebrated in such a way.

Then there is the method of commemoration that looks forward, that intrinsically understands history as a constant process, unfolding in this way or that depending on who pushes, who is pushed, and whether they are willing to push back. Not events as blueprints, but as ruptures and openings though which we can see a different future.

Read moreWhen I was a kid, I read a spoof in a nickelodeon about what it was like to watch a World War Two film with a German Shepherd. The punchline was that the dog always rooted for the wrong side. Viewing Hulu’s adaptation of Margaret Atwood’s 1985 sci-fi novel, The Handmaid’s Tale, I couldn’t help but to think of all the viewers who were sharing a sofa with friends, family, and lovers, who, openly or not, may view Gilead, the theocratic, dystopic, man-scape setting for the story, with a palate falling well short of the distaste intended by the filmmakers.

Read moreThe opening page of War Primer contains a short, four-line poem:

Like one who dreams the road ahead is steep

I know the way Fate has prescribed for us

That narrow way towards a precipice.

Just follow. I can find it in my sleep.

Read moreDenis Villeneuve’s Blade Runner 2049 is the much-anticipated sequel to the 1982 cult film directed by Ridley Scott. Like the original, 2049 is a visually stunning depiction of our potential dystopian future; one that if we read it in its historical context provides for us a detailed cognitive mapping of the continued decline of unfettered multinational capitalism. Also, like the original, the new film provides a surface level portrayal of the world that, if read in spatial terms, maps for us many of the contours of the rhizomatic networks of contemporary capital...

Read more